Genetic Imprint of Early Indo-Aryans in Central, West and South Asia

reconsidering the Kulturkugel model

Introduction

In this article we will take a multifaceted approach to the issue of interactions between Eurasian steppe cultures of middle to late Bronze Age and the people of Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), evaluate the Kulturkugel model, and search for a genetic track of early Indo-Aryans. To analyze the ancient DNA samples we have used the formal tool qpAdm.1 As in our previous articles, the list of the IDs of the samples that have been used, the data sources and the qpAdm outputs of each chart, which include all the technical details needed to be sure of the validity of our models, can be found in the supplementary material.2

Proto-Aryans

As it is generally known, the most prominent and widely accepted theory on the homeland of Proto-Aryans (i.e. Proto-Indo-Iranics, the common ancestors of Iranic, Indo-Aryan and Nuristani speakers) among the scientific circles is the Pontic-Caspian Steppe theory in which the Sintashta culture that preceded the Srubnaya and Andronovo cultures is generally seen as the most likely candidate. There are good reasons for this and I will list but a few since it is not the main subject of this article.

Proto-Aryans were nomadic cattle and sheep herders with domesticated horses, unfamiliar with any sort of advanced structures like temples or palaces as we can subtract from the earliest Sanskrit and Avestan texts and etymologies. While the Bronze Age cultures from West Asia to South Asia were mostly sedentary with advanced cities and structures and no domesticated horses until the arrival of steppe migrants, the Eurasian steppe cultures of middle to late Bronze Age were nomadic pastoralists with cattle and domesticated horse.3 Some of the Aryan loanwords in Uralic languages are from the Proto-Aryan phase, which indicates again a northern homeland for Proto-Aryans.4 Sintashta is also generally associated with the invention of chariot which would become an important war machine especially for later Indo-Aryans.

Sintashta was not an isolate of course; it had close connections with neighboring Abashevo and Potapovka cultures whose genetic profiles are almost indistinguishable from that of Sintashta. The split between Indo-Aryan and Iranic branches has probably occured somewhere around 1900 BCE, which makes it reasonable to regard the populations of these three cultures as Late Proto-Aryan speakers. Based on archaeological evidence, it has been previously suggested that Poltavka culture could be representing an earlier phase of Proto-Aryans (or “Pre-Proto-Aryans,” a term I do not find plausible), but unlike the three later cultures, Poltavka’s population was genetically a continuation of Yamnaya (Western Steppe Herder, WSH) without any admixture from Globular Amphora culture (GAC), and its paternal lineages are almost completely different. Fatyanovo culture, on the other hand, seems to be the more likely candidate for the Early Proto-Aryans, based on its population’s autosomal genetic profile (0.7 WSH, 0.3 GAC) and paternal lineages (R-Z93).5

Since this “Aryan” term has been politicized a lot by some evil events in recent history, the word invokes in the minds of many the image of the “superior,” homogenously blonde, blue-eyed population that is meant to dominate others. The reality does not seem to match up with this image: most of ancient and modern Aryans (Indo-Iranics) were and are quite a dark people, and even Proto-Aryans were not phenotypically homogenous. Also, interestingly for a population that is meant to dominate others, in many Uralic languages, the word for “slave” (for instance, Finnish orja) comes from the word “Aryan” (ārya-) as a result of a general pattern we see among many populations, that is, using the ethnonym of a neighboring population, from which they generally capture their slaves, to refer slaves in general, like the English word “slave” being ultimately derived from the ethnonym “Slav.”6

This is not to say there were/are no blonde or “dominating” Aryans. Neither there is a causal link between blondness and dominance, and if there is a correlation, I am unaware of it. This was just to deal briefly with some of the false stereotypes.

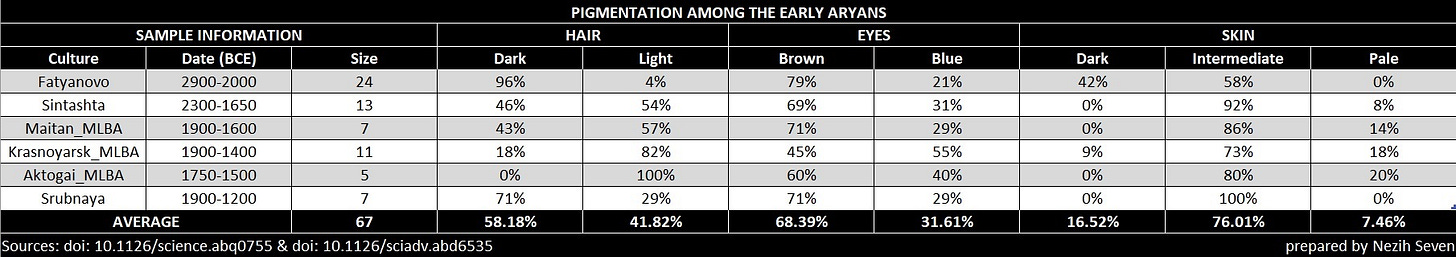

In the below table you can see the phenotypical diversity among the earliest Aryan populations (by “the earliest Aryan populations,” I mean Proto-Aryans and their descendants with a genetic profile that still was not significantly diverged from theirs).78 Listed cultures other than Fatyanovo and Sintashta cannot be considered Proto-Aryans since they are dated to after the Indic-Iranic split.

The Kulturkugel Model

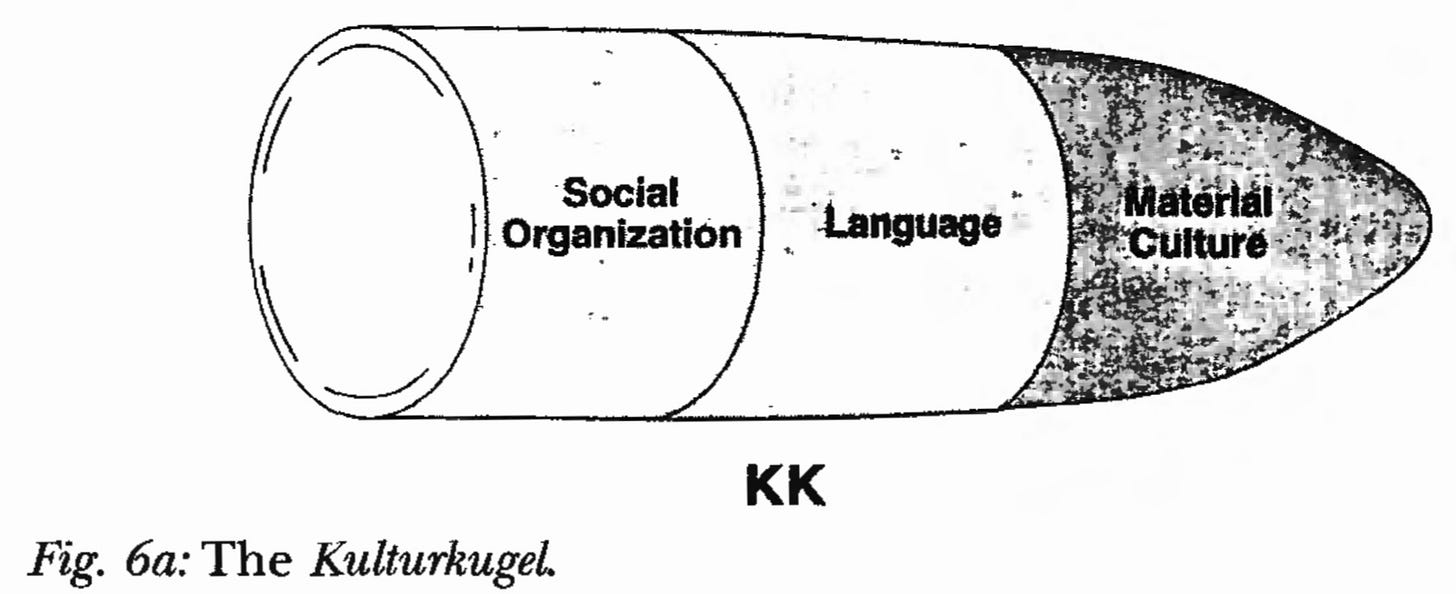

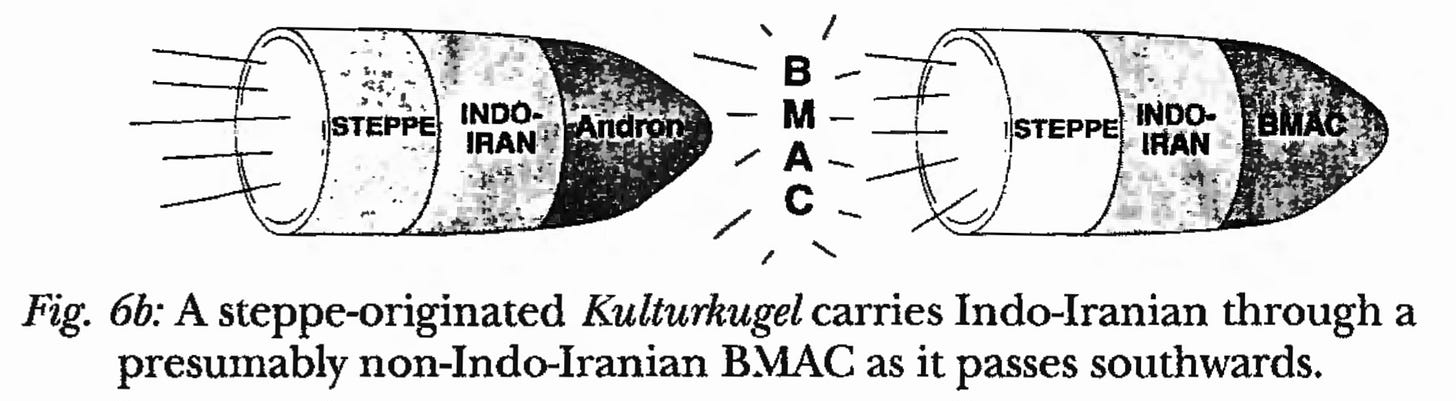

As soon as we accept the Pontic-Caspian Steppes as the homeland of Proto-Aryans, we have to face another problem: there is no strong archeological evidence for the expansion of this steppe culture to the lands known as Aryan-speaking for the most of history, except Central Asia. It certainly is possible to track an expansion from the steppe to Central Asia, and another expansion from Central Asia to both West and South Asia; but these do not seem to be the expansion of the same material culture. While the former is indeed the culture of the steppes, the latter is of BMAC. This led many scholars to see BMAC material culture as a carrier of the steppe language: basically early Aryans came to BMAC sites, there occurred a kind of amalgamation, and then this new social organism have adopted the language of the steppe and the material culture of BMAC. Mallory named this model as Kulturkugel, which means “culture bullet” in German (the language preference of his to name this model, in his own words, is due to enhance the respectability of an already shaky model):9

Kulturkugel… is envisaged as an explanatory projectile which is driven by social organization (here the type of hierarchical structure seen in the Sintashta burials which presumably extends to the creation of BMAC khanates, small fortress-states; Lamberg-Karlovsky 1994). It carries a linguistic package (here presumably Indo-Aryan) and, to pursue the metaphor farther, it has a nose of malleable material culture (Andronovo ceramics, metalwork, etc.). When, for example, an Andronovo Kulturkugel penetrated the BMAC (Fig. 6b), the force of its delivery (social organization) helped it carry through the BMAC with its linguistic package intact, although its material culture was shed or modified radically by that obtaining in the Central Asian sites. At the other end emerged a bullet, armed with a BMAC (cultural) head but otherwise carrying an Indo-Aryan language.

Linguistic Evidence

The first wave of Aryan migrations to the south was likely that of the Indic branch. Historical records indicate a class of charioteers who spoke a pre-Vedic Indo-Aryan language that was in control of the Mitanni kingdom in West Asia, approximately from 1600 to 1250 BCE. A cuneiform letter recovered from the archives of Tall Leilan in the Khabur Valley, Syria, speaks of these maryanni soldiers (likely related to Sanskrit marya-, “young man, young warrior, husband” with the ultimate etymological meaning of “mortal,” compare to Iranic counterparts, Kurdish mêr, “man, husband” and mirin, “to die” or Persian mard, “man, brave” from Old Persian martiya, “mortal, man”) that served Hurrian rulers as an elite troop, is dated to as early as 1760 BCE, much earlier than the estimations for the arrival of Iranic-speakers in the region. Another branch of later Indo-Aryans, on the other hand, has migrated to Swat Valley somewhere around 1400-1200 BCE and initiated the formation of the historical tribes that are known today as Rigvedic Aryans.10

Both archaeological and linguistic evidence point to a Central Asian route for the migration of Aryans. There is quite a number of loanwords in both early Avestan and Sanskrit that are borrowed from the same unknown non-Indo-European language, the majority of them indicating a culture, geography and architecture that match up with those of the BMAC. Contrary to widespread assumptions, these loanwords are not limited to agricultural and architectural terms; many religious terms of utmost importance related to the priestly caste and the most prominent ritual plant of Aryans seem to be derived from this language:11

The word soma/haoma (Sanskrit sóma, Avestan haoma) itself is inherited and simply means ‘squeezing, juice, extract’, but the name of the plant from which this juice was prepared is most likely borrowed (*anću). Also borrowed are the words *magha ‘ritual offering, sacrifice’, *atharwan ‘priest’, *ućig ‘priestly function’, *r̥ši ‘seer’, *bhišaj́ ‘medicinal herb’ (medicine was always the work of priests) and the names of some deities *Ćarwa, *Indra, *Gandharwa.

Although there is evidence for a cultural and mercantile network between Elamite, BMAC and Harappan worlds, there is no established genealogical relationship between this BMAC language and Elamite or Dravidian (or any other known language).

Compared with Avestan, the number of BMAC-derived words contained in the vocabulary of Vedic Sanskrit is higher. These additional BMAC-borrowings are mostly related to agriculture and likely point to the lifestyle changes of Indo-Aryans after their arrival in Swat Valley and Punjab. This would either mean that the pre-Aryan populations of Indus Valley and BMAC were speakers of related languages, or some BMAC people have joined to the migrating Indo-Aryan tribes on their way to northern South Asia and thus the contact period between their languages has become prolonged. Considering that the BMAC and Indus Valley Culture do not have much in common archaeologically, the latter scenario is more likely.12

The rest of the article is still free and hopefully will stay so, but if you have read this far and appreciated what you have seen, please consider supporting my work on Patreon.

I am an archaeologist who mainly works on ancient Indo-Iranic cultures. I have published many articles and videos on archaeogenetics and ancient religious traditions in English and Turkish, some of which have been translated into Kurdish and Persian. Eliminating the fallacies surrounding these areas of research (that are generally born out of ideological sentimentality or romanticism regarding one's own ancestors) and providing reliable information in a clear, systematic and analytical way are my main objectives. I would be more than glad if you choose to support my work!

May the xᵛarənah be with you!

Archaeological Evidence

Francfort distinguishes three principal periods of BMAC:13

Formative phase: 3000-2500/2400 BCE

Urban phase: 2500/2400-1700 BCE

Post-urban phase: 1700-1500 BCE

Based on the findings related to horse and chariot, Parpola assumes a presence of an Indo-Aryan elite in BMAC since the middle of its urban phase, around 20th century BCE:14

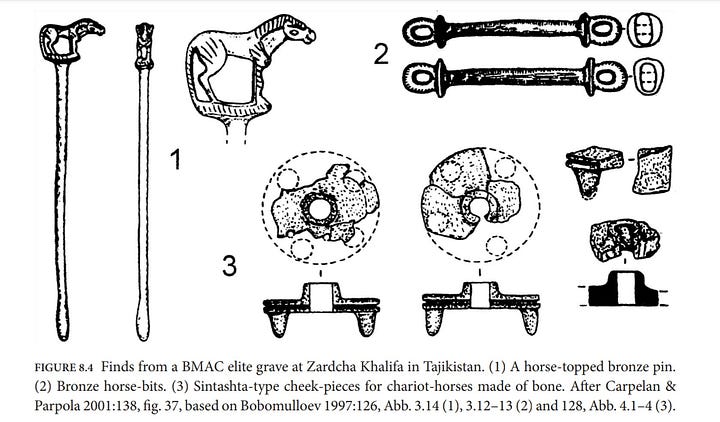

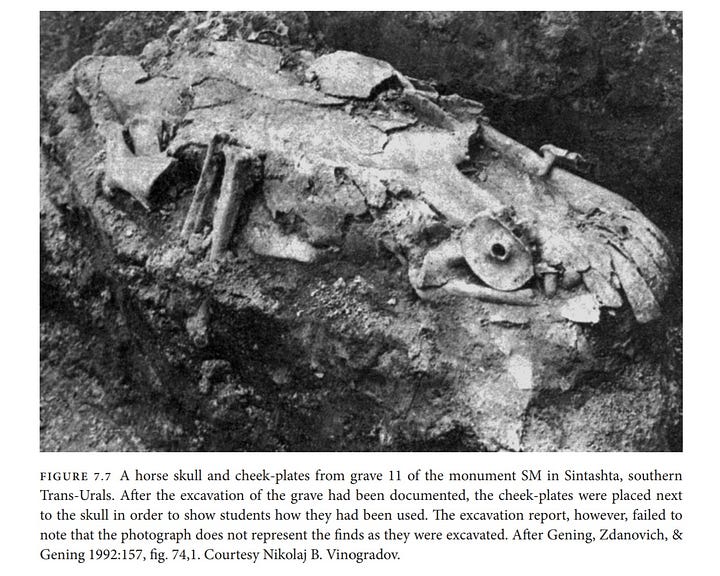

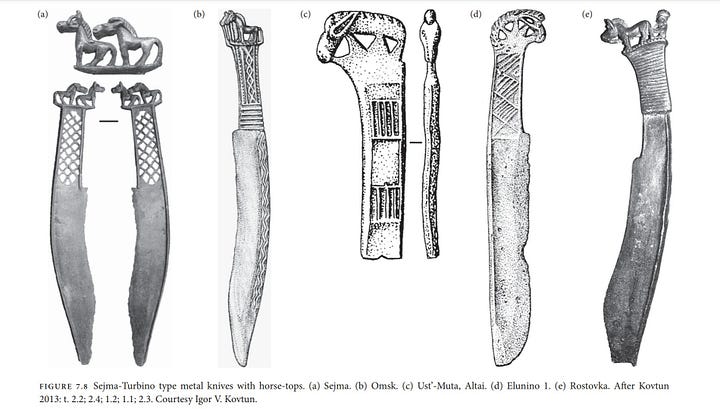

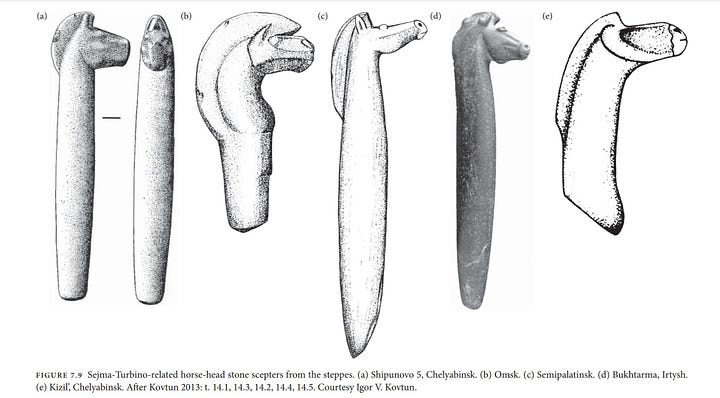

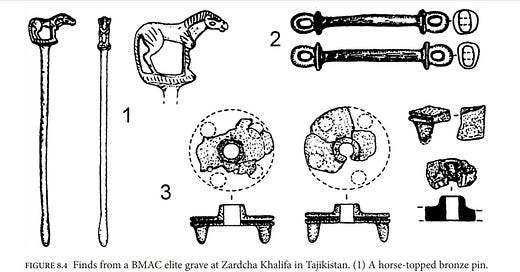

A rich grave accidentally found at Zardcha Khalifa in the Zeravshan Valley in Tajikistan (Bobomulloev 1997) contained, besides ceramics and other grave goods typical of the BMAC (Sarianidi 2001:434), the remains of a chariot and two horses, which once had cheek-plates (psalia) of precisely the same type as at Sintashta culture, and mouth bits (Fig. 8.4; cf. Fig. 7.7). In addition, there was a bronze pin, whose horse-top is paralleled by the horse-tops of the Sejma-Turbino knives and scepters (Figs. 7.8, 7.9). This find suggests that Indo-Aryan speakers had come from the southern Urals and entered the ruling elite of the BMAC probably as early as the twentieth century bce. Sintashta-type cheek-plates have recently been excavated also in grave 2 at Sazagan in the Zeravshan Valley, here too with BMAC ceramics of the Sapalli phase (c. 2000–1800 BCE) (Avanesova 2010).

Parpola’s estimation for the date of Indo-Aryan arrival in BMAC sites corresponds with its expansive period (1900-1750 BCE), in which the dynamism and aggressiveness of BMAC increased and its material culture got more and more pervasive:15

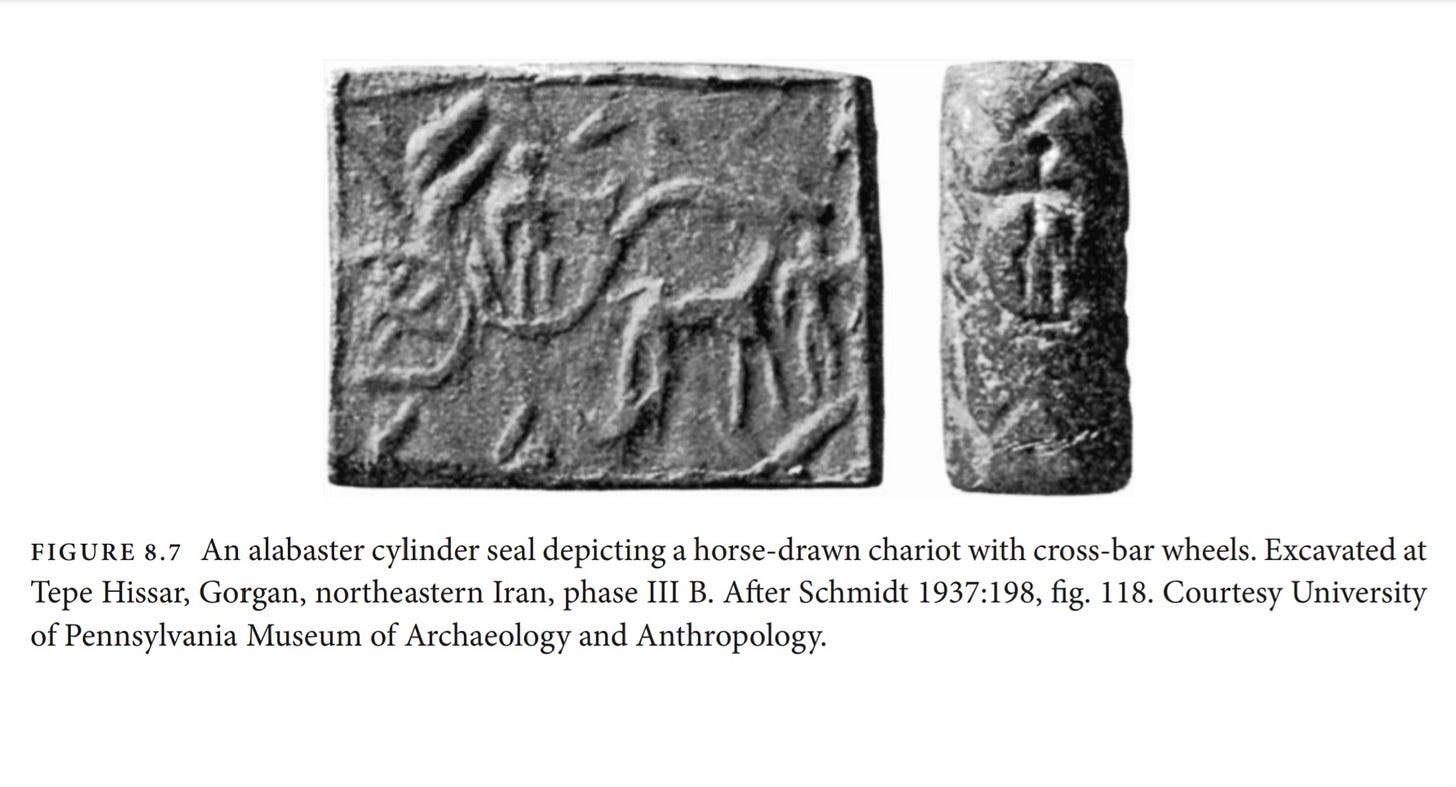

The BMAC expanded to the Gorgan region near the southeastern shore of the Caspian Sea in northern Iran, where it is represented by the Tepe Hissar IIIC culture (c. 1900–1750 bce). The large number of its bronze weapons suggests that this rich culture was ruled by a warring aristocracy (Schmidt 1937). An alabaster cylinder seal excavated from the IIIB phase at Tepe Hissar depicts a two-wheeled horse-drawn chariot (Fig. 8.7)… Ghirshman also proposed that the Indo-Aryan-speaking nobles of the Mitanni kingdom of Syria came from the Tepe Hissar IIIC culture…

Cuyler Young (1985) has plausibly linked the arrival of these Indo-Aryans in Syria with the sudden appearance of the Early West Iranian Gray Ware in great quantities all along the Elburz Mountains, in Azerbaijan, and around Lake Urmia around 1500 bce. Young sees this ceramic, which is new to western Iran, as an evolved form of the Gorgan Gray Ware of the Tepe Hissar IIIC phase, which continued in an impoverished form at Tureng Tepe until about 1600 bce. Young’s reconstruction provides a chronologically and typologically acceptable link between the Mitanni Aryans, the Tepe Hissar III culture of Gorgan, and the BMAC.

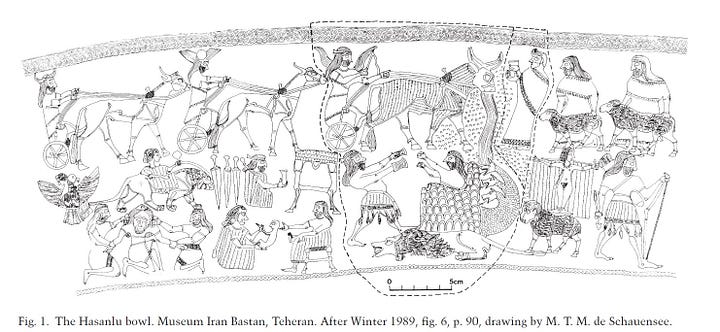

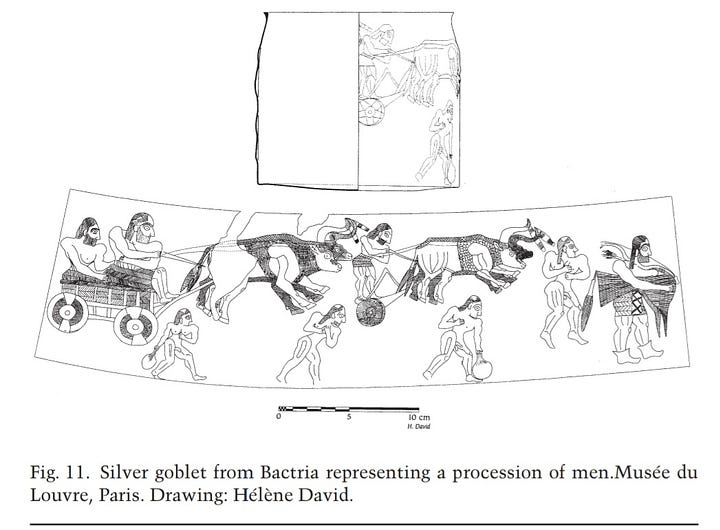

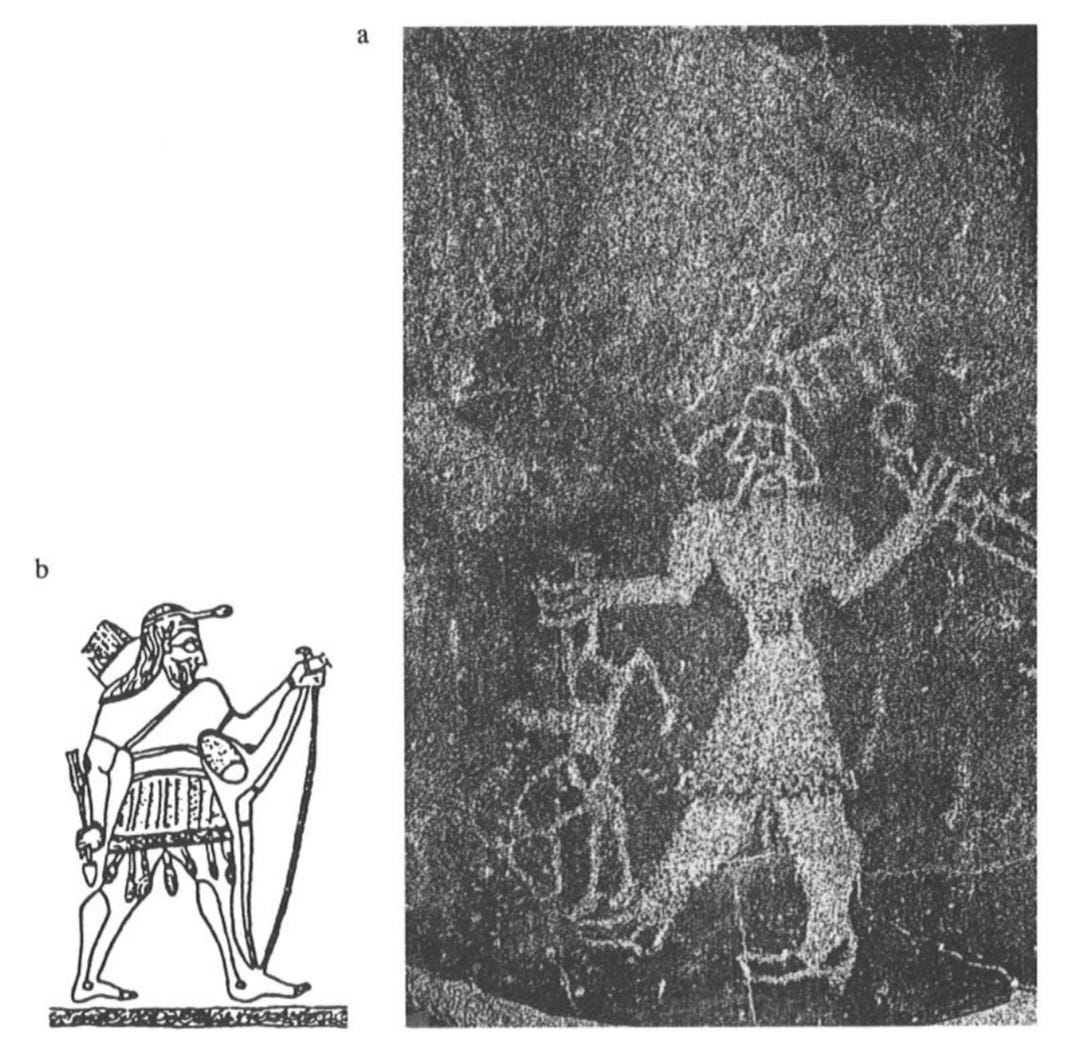

In the previous article, I had mentioned the Hasanlu Bowl, which was found in Hasanlu, near Lake Urmia, and interpreted by names like Dumézil, Francfort and Parpola as displaying some Indo-Aryan characteristics (on top of its Hurrian layer).16 For instance, Francfort interprets the upper register of the bowl as representing the Indo-Aryan gods Indra, Mitra, Varuna and Nāsatya. But, most importantly, the bowl shows strong signs of BMAC iconography, which again strengthens the proposed BMAC-Mitanni relationship: a celestial goddess providing water, vegetation and animals and tames a dragon; a dragon retains waters-fertility; a hero partly bird of prey and partly human fights with the dragon. Also the hero depicted on the bowl wears a kilt ornamented with what apparently are animal tails, which is the costume of BMAC warriors:17

Interestingly, archaeologists have compared the figure on a petroglyph found in Chilas, Gilgit-Baltistan, to the hero of Hasanlu Bowl. Besides the general iconographic similarity, the figure on the Chilas petroglyph wears a similar headdress with its snake-like forward projection:1819

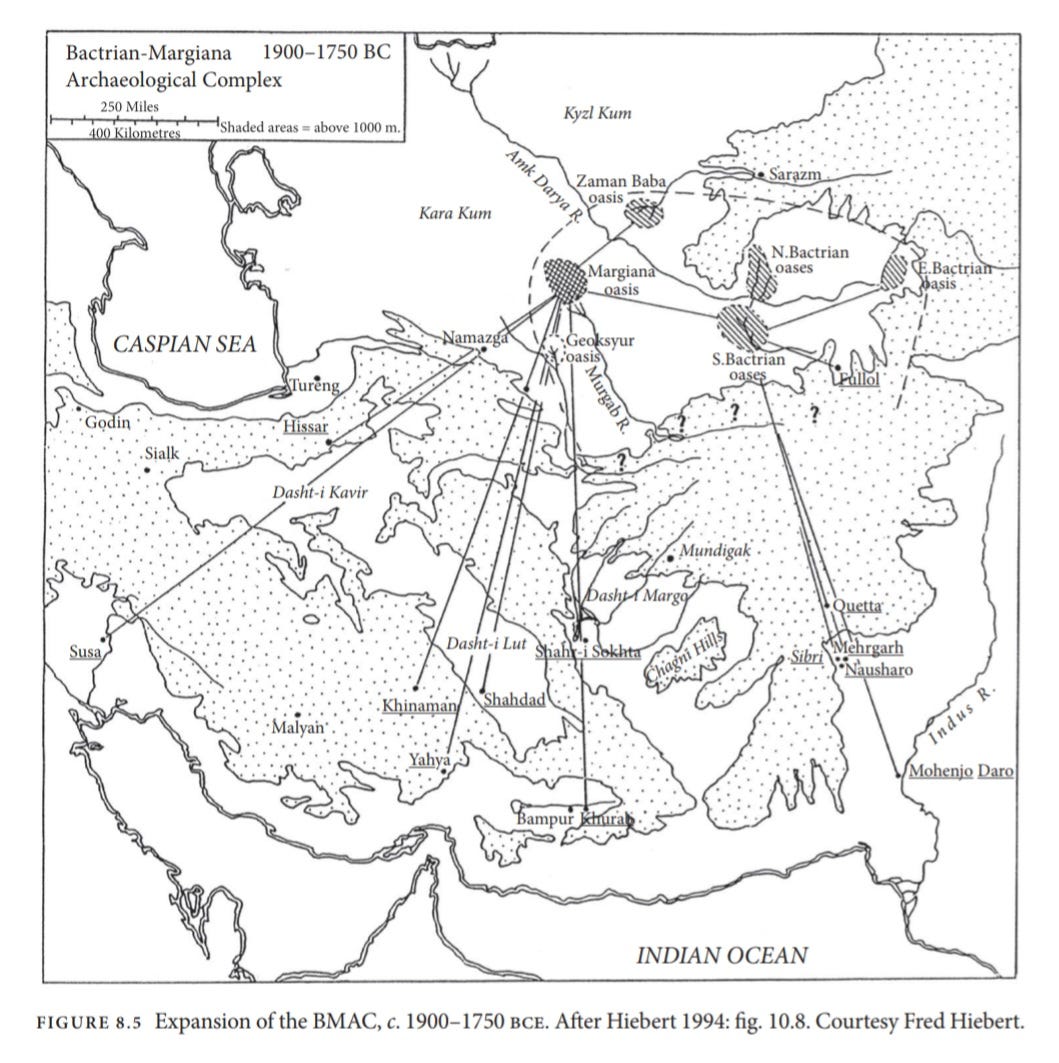

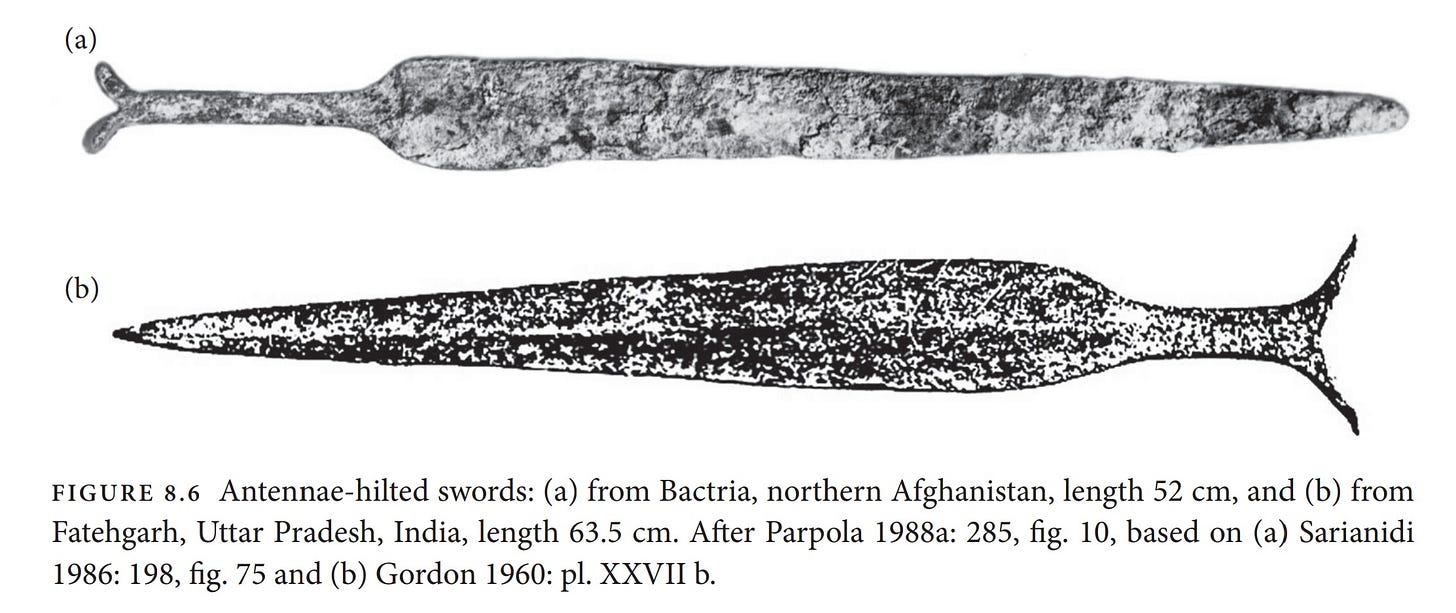

During 2000–1900 bce, the BMAC spread to Pakistani Baluchistan. A rich BMAC graveyard was accidentally discovered at Quetta, while other BMAC graves were found at Mehrgarh VIII and Sibri near the Bolan Pass. That BMAC people (not just traders) moved to Pakistani Baluchistan is evident from the fact that the entire cultural complex was imported, including burials (Jarrige 1991). BMAC-type seals and seal impressions have been found in small numbers in the late phase of the Indus civilization at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa (Parpola 2005d; Franke 2010), and in post-Harappan times in the southern Indus Valley (the so-called Jhukar seals in Chanhu-daro) (Mackay 1943), Gujarat (Somnath, alias Prabhas Patan), and even Rajasthan, where about a hundred seal impressions were collected in a pot at Gilund (Shinde, Possehl, & Ameri 2005) (Fig. 8.5). The Gangetic copper hoards have antennae-hilted swords similar to those coming from plundered BMAC sites of Afghanistan, which dates the hoards to about the twentieth century bce or later (Fig. 8.6).

The Gandhara Grave culture of the Ghālegay IV phase (c. 1700–1400 bce) in the Swat Valley starts with the arrival of a new culture, one of the first in South Asia to show clear evidence for domesticated horse, in motifs of painted pottery as well as in bone finds. Two well-preserved horse skeletons were excavated in the Kātelai graveyard of Swat (surface stratum). The black-gray, burnished pottery introduced from the beginning of phase IV is present throughout Swat and has been connected with the pottery of the late “urban” phase of the BMAC culture widespread in the surrounding areas at this time, for example at Dashly in Afghanistan and Tepe Hissar and Tureng Tepe in northern Iran. In the Ghālegay IV Period graveyard at Kherai in Indus Kohistan, the inhumed bodies are placed on their sides in a flexed position, this burial custom being typical of the BMAC in southern Bactria. Besides the gray-burnished ware, the Ghālegay IV Period had black-on-red painted pottery related to the Cemetery H culture of the Punjab plains (Fig. 4.4). The horse is depicted on several shards of this kind of ceramics at Bīr-kōṭ-ghwaṇḍai in Swāt. Very typical of the Gandhāra Graves are the metal pins for fixing clothing; such pins are known from the BMAC necropolis at Gonur and as imported foreign objects from graves in Syria (Chagar Bazar). The terracotta female figurines have close parallels in the BMAC necropolis of Gonur, at Tepe Hissar III in northern Iran, and in Syria. A compartmented metal seal of the BMAC type was recently found in Chitral.

All the archaeological evidence point to the expansion of BMAC material culture to both West and South Asia, along with its burial practices in some of these examples of penetration. Interactions between steppe migrants and BMAC people, on the other hand, seem to be largely peaceful. There is little evidence of violence. In the post-urban phase of BMAC, practically all settlements in south Turkmenistan were surrounded by campsites with late Andronovo ceramics. The inhabitants of the central city of BMAC at Gonur Depe, located in the old delta of Murghab River, were abandoning their city in this post-urban phase because of the desiccation due to the movement of the riverbed to eastwards that likely began around 1800 BCE.20

Genetic Evidence

Autosomal DNA

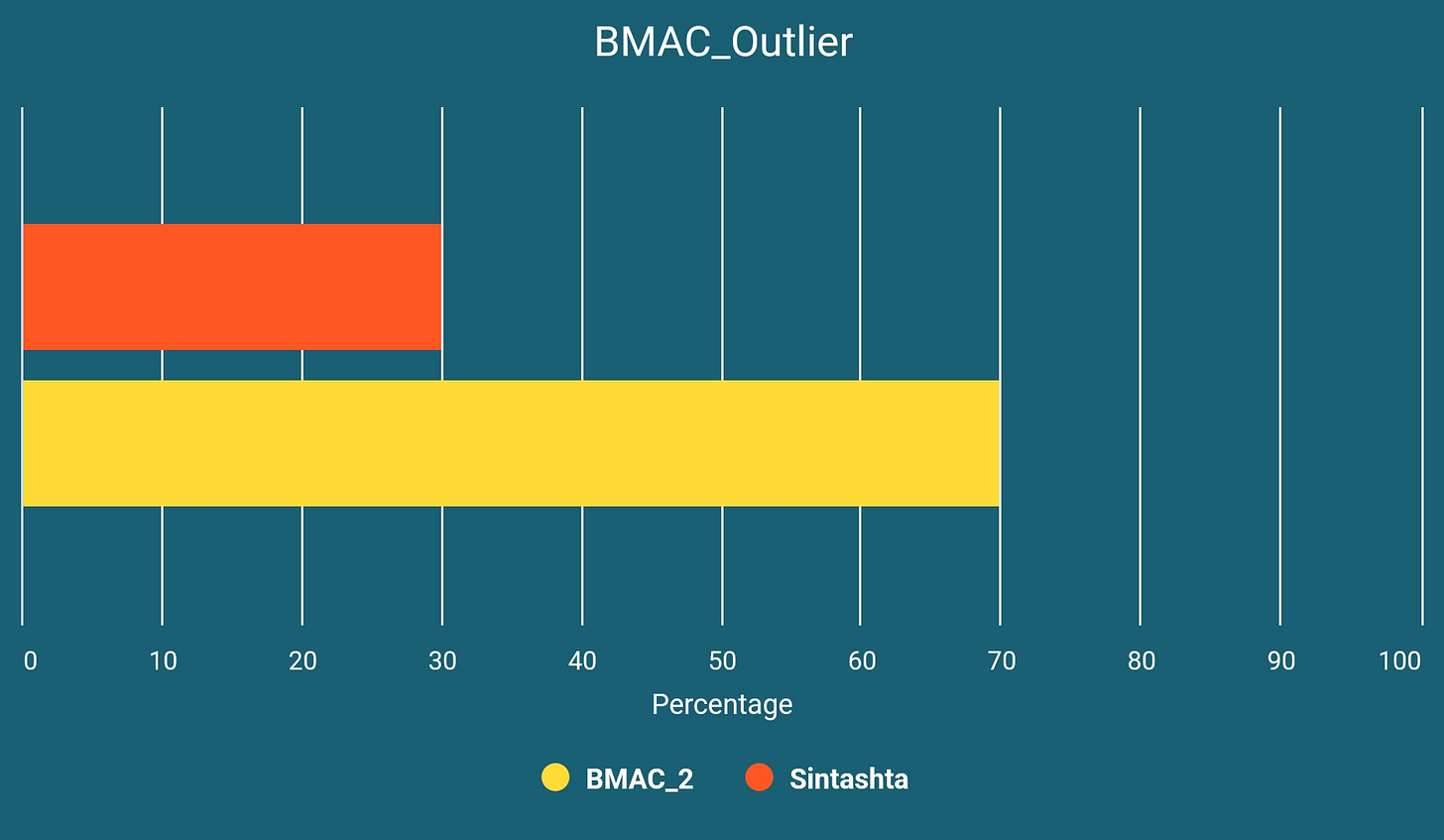

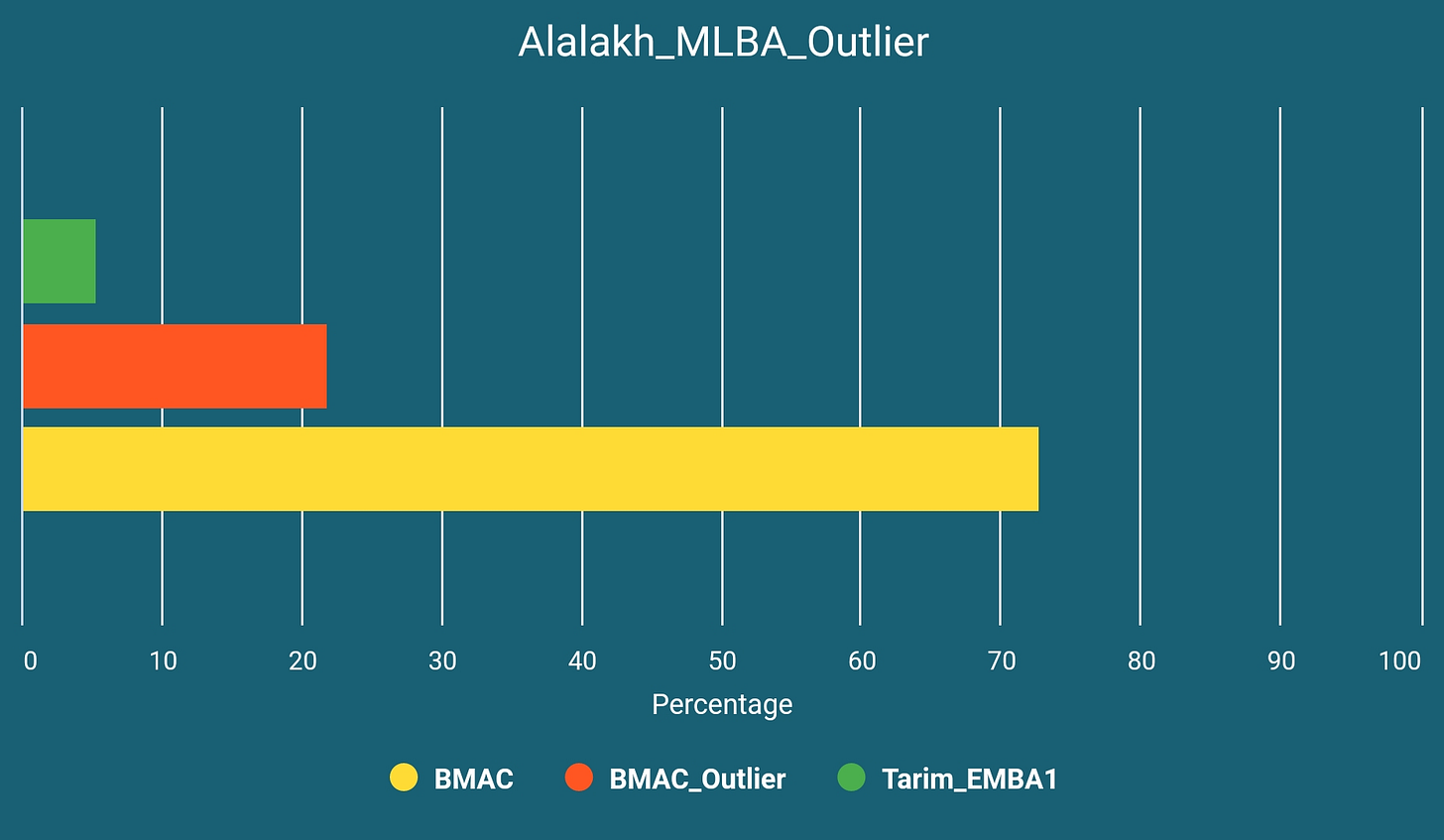

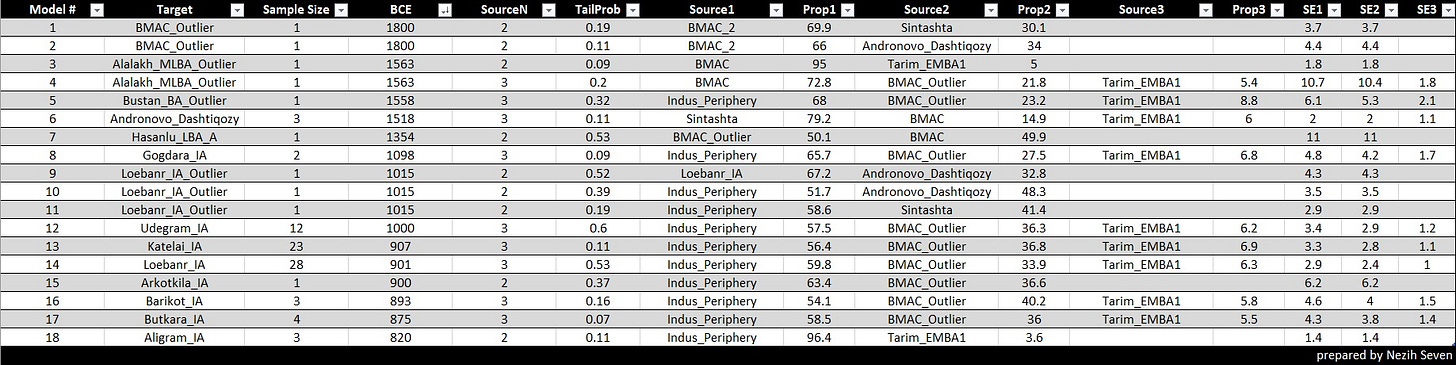

The main population of BMAC settlements can be modeled as having 0.65 Neolithic Zagrosian, 0.25 Neolithic Anatolian Farmer (ANF) and 0.1 Western Siberian Hunter-Gatherer (WSHG) ancestries without any Steppe Pastoralist admixture.21 By the turn of the second millenium BCE, however, this steppe ancestry begins to appear in outlier individuals. An outlier male sample (BMAC_Outlier, ID: I7493) from Sapalli Tepe, dated to 2000-1600 BCE, mostly corresponding with the late urban phase of BMAC, can be modeled as below (please note the Sintashta-type cheek-plates with BMAC ceramics of the Sapalli phase mentioned above):

This BMAC outlier has been assumed by some to be an ancient Iranic sample because of its genetic proximity to many modern Western Iranics. This is a false reasoning for two basic reasons: 1. Genetic proximity is not necessarily an indicator of a direct genealogical relatedness; it might well occur due to separate admixtures of different populations with ancestries that are related in a past that is much deeper, and 2. Considering the migration routes, it is nothing but reasonable to expect from early Indo-Aryans and Iranics to have a similar genetic profile. Therefore, it is crucial to have some knowledge about the histories and material cultures of the relevant populations before speculating on the ethnicity of an ancient sample based on its DNA. The urban phase of the BMAC is too early for the generally accepted date for the arrival of Iranics in the region, and thus we can conclude that it is more likely an Indo-Aryan sample.

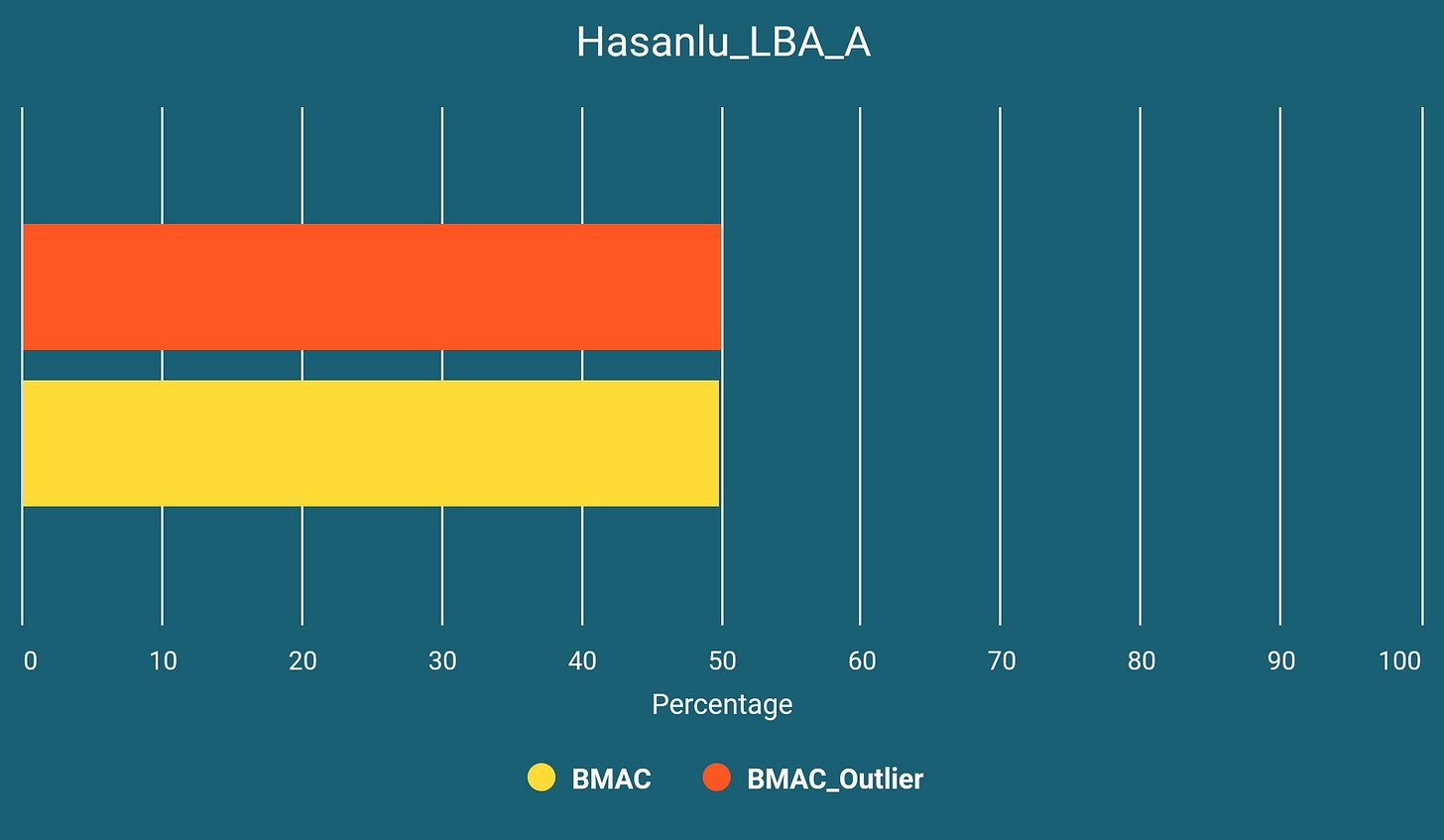

In the previous article, I had analyzed a late Bronze Age sample (Hasanlu_LBA_A, ID: I4097) from Hasanlu, Northwestern Iran, dated to 1425-1284 BCE, that resembling a Central Asian migrant, possibly related to Mitanni Aryans.22 It had been successfully modeled as having around 0.85 BMAC and 0.15 Sintashta ancestries. In fact, the BMAC outlier from Sapalli Tepe seems like an effective intermediary for the source of steppe ancestry of this sample from Hasanlu:

There is another ancient DNA sample (Alalakh_MLBA_Outlier, ID: ALA019) of a Central Asian migrant from West Asia, this time Alalakh, Southern Turkey, sometimes referred to as the lady in the well since this migrant was a violently killed female whose bones have been found at the bottom of a deep well. It is dated to 1616-1510 BCE and has been speculated to be related to Mitanni Aryans. Considering the date, location and Central Asian genetic profile, it is quite possible, and it can be modeled as, again, having some ancestry related to the BMAC outlier we have analyzed above:

It should be noted that this sample can be modeled without any steppe-related ancestry, although it causes the p-value drop (lower p-values do not necessarily indicate less realistic scenarios). Alternative models for the analyzed samples are included in the Table 2.

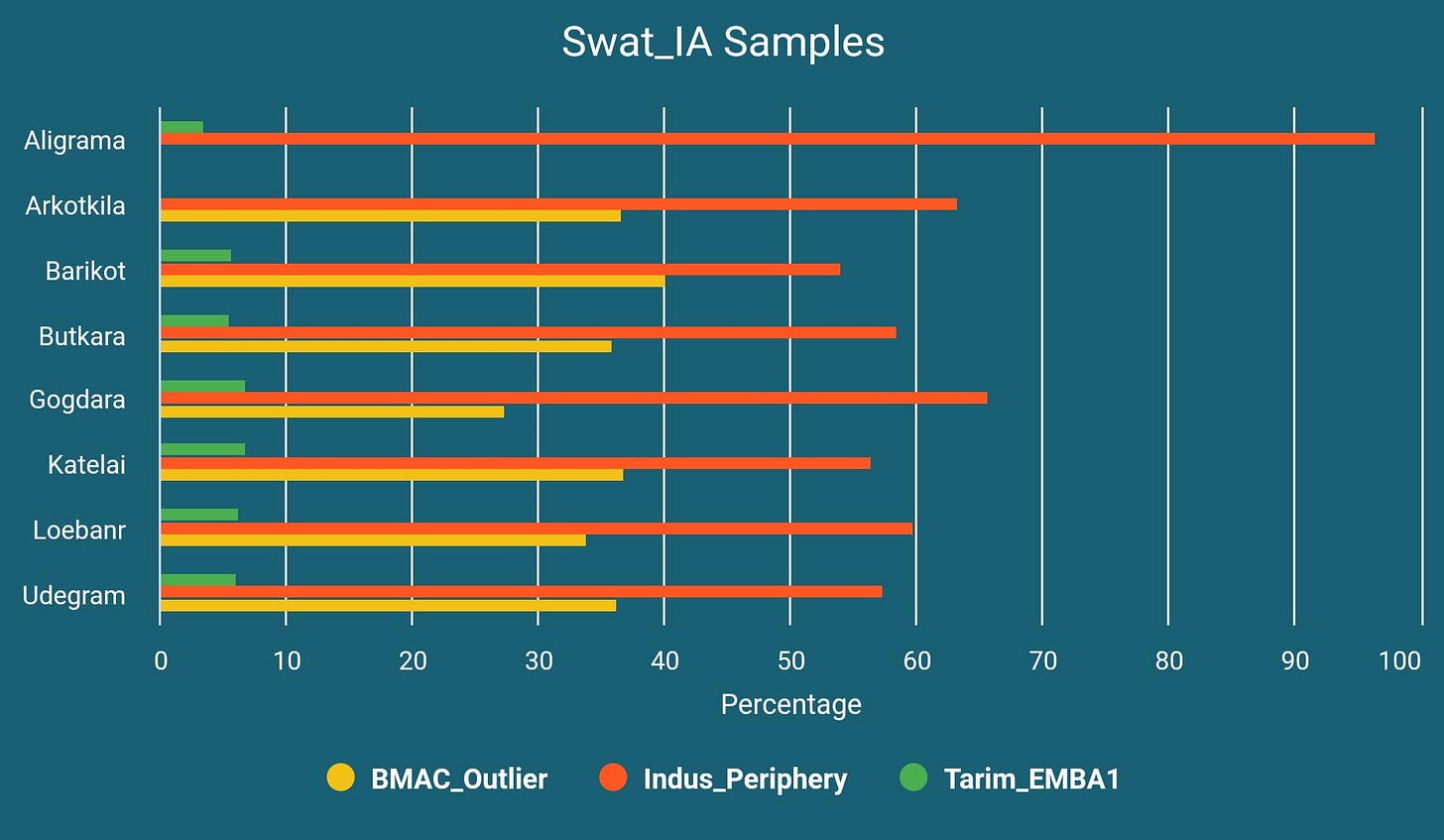

I also have analyzed a total of 77 samples from different Iron Age Swat Valley sites (Pakistan), dated to 1400-800 BCE, where we would certainly expect to find Indo-Aryans. Except three samples from Aligrama, all seem to have significant ancestry derived from a BMAC_Outlier-like source.

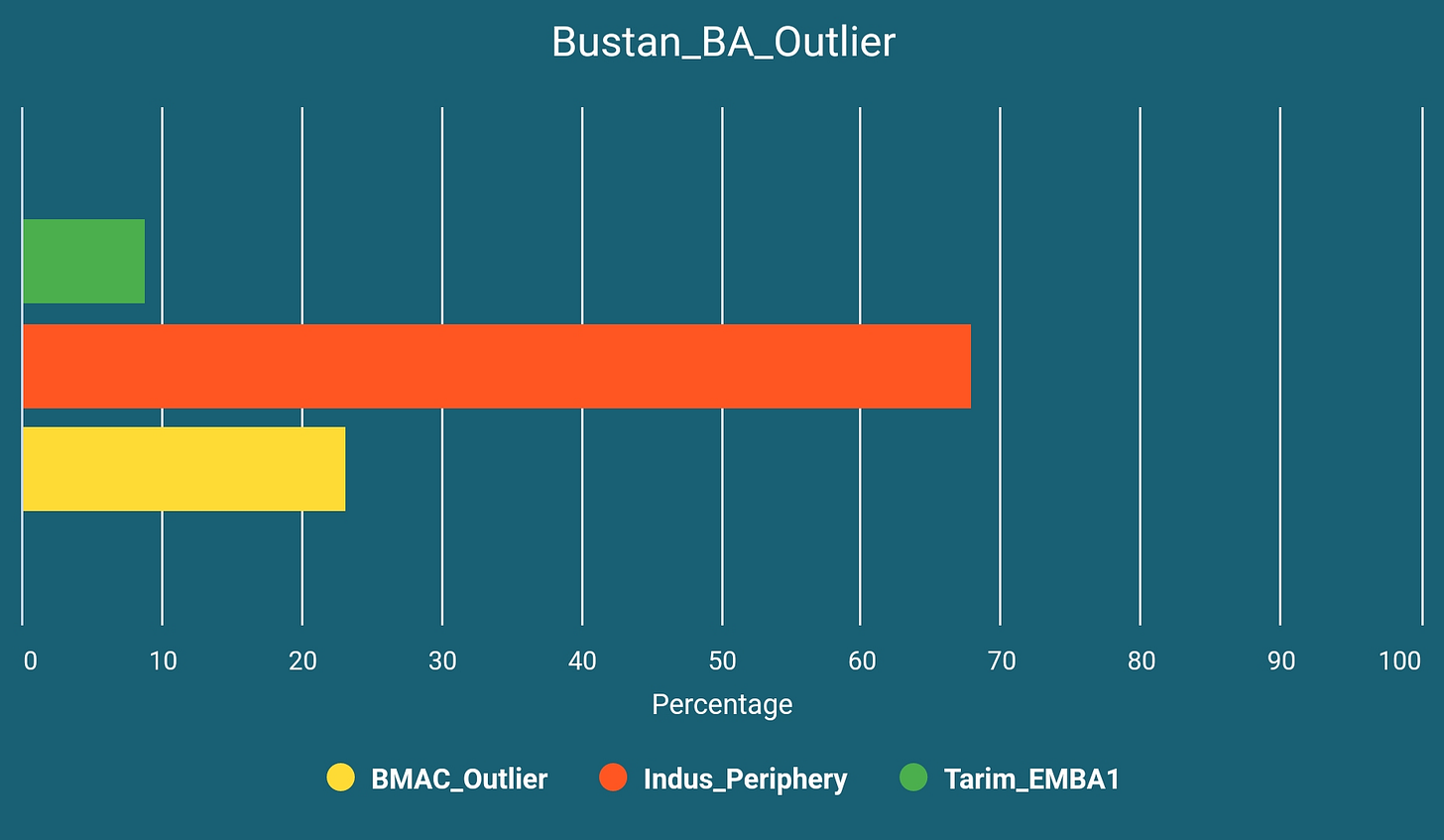

An earlier outlier sample (Bustan_BA_Outlier, ID: I11520) from Bronze Age Bustan, Uzbekistan, dated to 1613-1503 BCE, also displays a similar genetic profile to the main Swat_IA cluster, although with lower BMAC_Outlier-like ancestry.

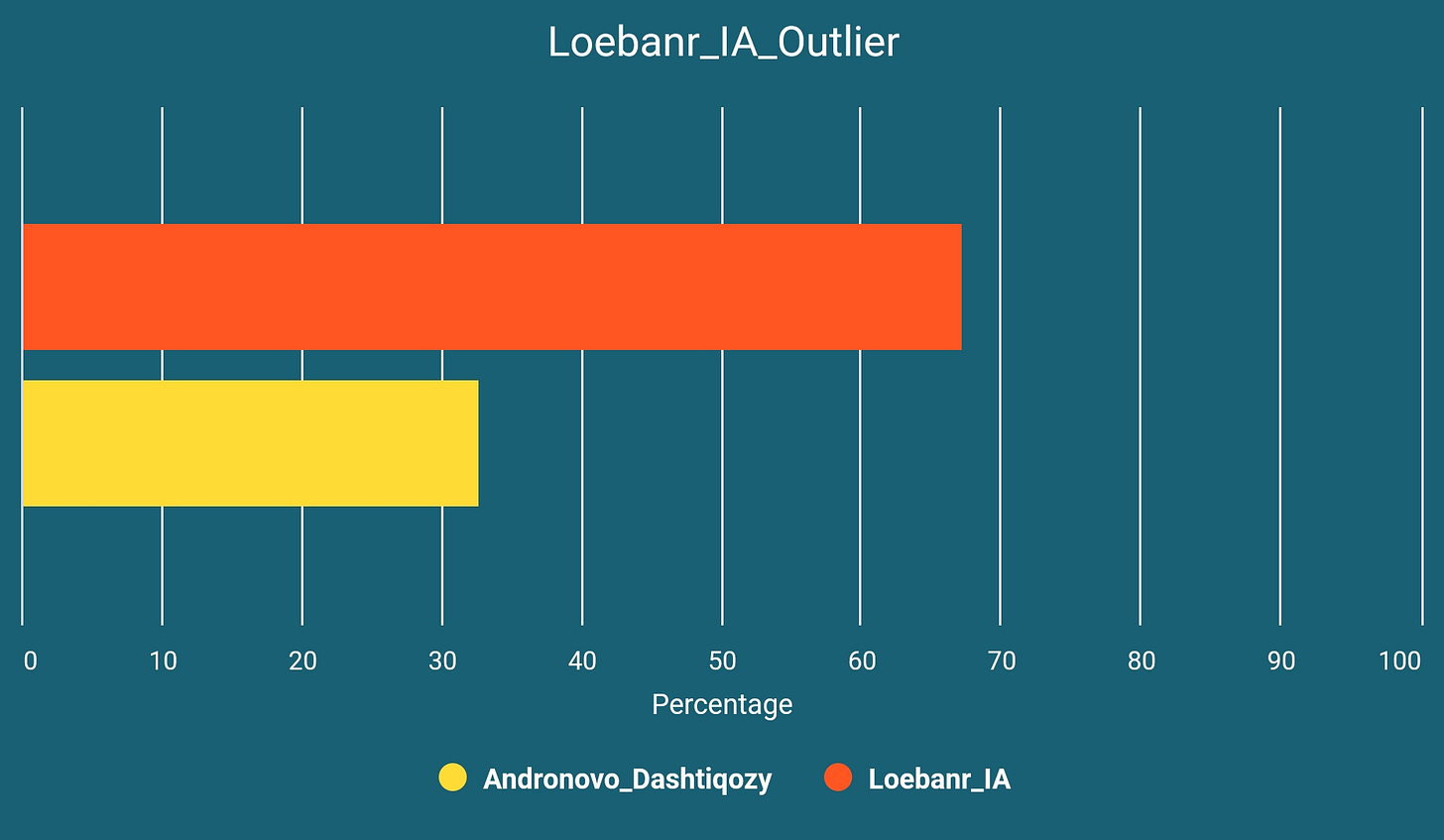

An outlier sample (Loebanr_IA_Outlier, ID: I12138) from Iron Age Loebanr, dated to 1107-924 BCE, on the other hand, has significant additional steppe admixture on top of the main Loebanr_IA ancestry.

In most cases, BMAC_Outlier seems like a proper intermediary for the steppe ancestry of the ancient samples that are likely of Indo-Aryan speakers.

Y-DNA

When it comes to Indo-Iranics, it is generally assumed that the only possible Y-DNA marker can be the steppe-related R-Z93. There is no reason, however, to assume that later Indo-Iranics were all paternally steppe-derived, especially when considered the mostly peaceful relationship between steppe nomads and BMAC people. After all, R-Z93 is not the only paternal lineage among modern Indo-Iranics, and therefore there is no logical necessity forcing us to think that for any given Indo-Iranic presence in history, the Y-DNA R-Z93 must also be seen (especially when the sample size is small). It should be accepted that the Y-DNA diversity can increase in a population for a variety of reasons.

The databases I have used for below inferences are specified in the footnotes.232425

The Y-DNA of BMAC_Outlier is Q-Z19128, and actually this is the most ancient known example of this subclade. Interestingly, two samples from Iron Age Loebanr (IDs: I13228 & I5400) that are approximately thousand years younger are also carriers of the same subclade. The most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) of this subclade is dated to around 3700 BCE, 900 years earlier than BMAC_Outlier, and therefore there seems to be a meaningful connection.

The Y-DNA of Hasanlu_LBA_A is J-ZS6592. Four samples with the same subclade predating Hasanlu_LBA_A are all from Central Asia, three belonging to Namazga Culture (periods III-IV, 3500-2800 BCE, IDs: I12481, I12487, I8524) that is ancestral to BMAC, and one to the urban period of BMAC (ID: I1784). TMRCA is dated to around 4700 BCE, which, again, indicates a meaningful connection between BMAC and this Hasanlu sample.

The Y-DNA of Bustan_BA_Outlier is R-FGC17608. The most ancient known sample with this subclade is from Namazga Culture (periods III-IV, 3400-2800 BCE, ID: I8526) that is ancestral to BMAC. TMRCA is dated to around 6600 BCE, which is more than three thousand years earlier than the most ancient known carrier of this subclade, and therefore it might not be a meaningful connection. Still it should be noted that two Iron Age samples from Katelai (IDs: I12147, I12462) are found to carry a descendant clade, R-V3714 (TMRCA: 6250 BCE).

An Iron Age Katelai sample (ID: I12465) is a carrier of J-Z7706. The most ancient known samples with this subclade are from Tepe Hissar, Iran (ID: I2337, dated to 3640-3518 BCE) and BMAC (ID: I7494, dated to 2016-1830 BCE). This BMAC sample is one of the labeled ones as BMAC_2 in this article. TMRCA is dated to around 5750 BCE. There might be a connection.

Eight samples from Iron Age Swat Valley (IDs: I10974, I12459, I12988, I10523, I10000, I10001, I6555, I6554) are carriers of L-Y87534, which has a common ancestral clade with L-FT351270 (TMRCA: 4550 BCE), the subclade that is carried by a later Hasanlu sample (ID: I4233, dated to 902-812 BCE) and a sample from Orontid era Karmir Blur, Armenia (ID: I16119, dated to 399-231 BCE). Their most recent common ancestral clade is L-Y6288 with TMRCA being dated to around 5200 BCE. There is approximately seven hundred years between the most recent common ancestors of L-FT351270 and L-Y6288; there might be a connection. It should be noted that the ancestral clade to L-Y6288 is L-M357 with TMRCA dated to around 5400 BCE, only two hundred years earlier than L-Y6288’s. The most ancient three known carriers of L-M357 are all BMAC samples (IDs: I11463, I5604, I4285). Five other Iron Age Swat Valley samples (IDs: I13223, I12445, I12475, I13222, I8220) are also found to be carriers of L-M357, with descendant clades remaining undetermined.

Another later Hasanlu sample (ID: I6428, dated to 1115-932 BCE) also carries a seemingly BMAC-related Y-DNA, J-BY40968. Two known earlier samples are both from BMAC (IDs: I11474, I10411, dated to BMAC’s formative and urban phases, respectively). TMRCA is dated to around 4000 BCE.

Two samples from Iron Age Swat Valley (IDs: I12450, I12457) are found to be carriers of Sintashta-related R-Z94.

Conclusion

Both linguistic, archaeological and genetic evidence seem to agree on close connections between, and even amalgamation of, the steppe migrants and BMAC people. Most likely early Indo-Aryan-speaking steppe nomads have arrived in the BMAC region around 2000 BCE, not necessarily as rulers, but at least as troops of elite warriors with their effective war machines and social structures. This is when we see the steppe DNA first in the region and also the expansion of the BMAC material culture, which might be indicating the emergence of a new society, a BMAC Kulturkugel carrying Indo-Aryan languages, where the warlike inclinations of the steppes meet the advanced culture of ancient Central Asia; a synthesis that will later express itself also in the religious languages of the Avesta and Vedas. With the desiccation that began around 1800 BCE, BMAC sites gradually became less and less populated, with its population likely joining the surrounding Indo-Aryan tribes to migrate with them: a scenario that can explain the prolonged contact between BMAC and Indo-Aryan languages. Due to the mass adoption of nomadic pastoralism and effective warrior societies, in other words, assimilation into the structures of the steppe people, the language of the nomadic warriors eventually became the dominant one in this amalgamation. Ancient DNA samples from locations where we would expect to find ancient Indo-Aryans display both steppe and BMAC-related admixture with no male steppe bias (this is not a general claim for all possible steppe-BMAC admixtures), which strengthens the probability of this scenario.

Harney, É., Patterson, N., Reich, D., Wakeley, J. (2021). Assessing the performance of qpAdm: a statistical tool for studying population admixture. Genetics, 217 (4), https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyaa045

Seven, N. (2023, May 12). Supplementary Material for Genetic Imprint of Early Indo-Aryans in Central, West and South Asia. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1rZEp7shB-SY3tbisonqActZJztg916tO?usp=sharing

Kuzmina, E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Brill.

Parpola, A. (2020). Royal “Chariot” Burials of Sanauli Near Delhi and Archaeological Correlates of Prehistoric Indo-Iranian Languages. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 8 (1), https://doi.org/10.23993/store.98032

Saag et al. (2021). Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain. Sci. Adv. 7, (4), DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abd6535

Parpola, A. (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press.

Saag et al. n (5)

Lazaridis, I. et al. (2022). The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe. Science, 377 (6609), DOI: 10.1126/science.abm4247

Mallory, J.P. (1998). A European Perspective on Indo-Europeans in Asia. In V.H. Mair (Ed.), The Bronze and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern Central Asia, vol. I. pp. 175-201. Institute for the Study of Man.

Parpola, A. n (6)

Lubotsky, A. (2020). What Language Was Spoken by the People of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex? In P.W. Kroll and J.A. Silk (Eds.), At the Shores of the Sky, pp. 5-11. Brill.

Lubotsky, A. n (11)

Francfort, H.P. (2005). La civilisation de l’Oxus et les Indo-Iraniens et Indo-Aryens. Pp. 253–328 in: Fussman et al. 2005.

Parpola, A. n (6)

Parpola, A. n (6)

Seven, N. (2022, December 1). A Genetic Analysis of Historical Population Movements Around The Zagros Mountains. Genetics of Eran, Turan and Rum.

Francfort, H.P. (2008). A Note on the Hasanlu Bowl as Structural Network: Mitanni-Arya and Hurrian? Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 22, pp. 171-188.

Parpola, A. (2015). The Coming of the Aryans to Iran and India and the Cultural and Ethnic identity of the Dāsas. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 64, 195–302. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/store/article/view/49745

Parpola, A. n (6)

Lubotsky, A. n (11)

Narasimhan, Vagheesh M. et al. (2019). The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia. Science, 365 (6457), https://doi.org/10. 1126/science.aat7487

Seven, N. n (16)

Ancient Y-DNA and mtDNA. (2023, May 7). Indo-European.eu. https://indo-european.eu/ancient-dna/

YFull: NextGen Sequence Interpretation. (2023, May 7). https://www.yfull.com/

FamilyTreeDNA Discover. (2023, May 7). https://discover.familytreedna.com/

"unfamiliar with any sort of advanced structures like temples or fortresses as we can subtract from the earliest Sanskrit and Avestan texts and etymologies."

This can be disproved with a quick ctrl+f.RV Book 10.107.10 :"This dwelling of the benefactor is like a lotus-pond, adorned and shimmering like the palaces of the gods"

RV Book 7. 88.5: "O Varuṇa of independent will, I went into your lofty mansion, your house with its thousand doors."

The same palace in the Avesta, Yasht 5. 101: "In each channel there stands a palace, well-founded, shining with a hundred windows, with a thousand columns, well-built, with ten thousand balconies, and mighty."

^ Doesn't sound like a Sintashta hut.

Many of these supposed BMAC loanwords have proposed IE etymologies such Indra and ustra. Assuming there is a substrate can we for sure say it's from BMAC? What if BMAC was Indo-Iranian and this substrate comes from Vakhsh culture, SiS, Mundigak..etc? After all, much of the "high culture" elements of BMAC have their roots in Mundigak.

Also, there isn't a consensus on the Aryan words in Uralic. Depending on the linguist they range from Proto-I-I to middle Iranian.

"Most likely early Indo-Aryan-speaking steppe nomads have arrived in the BMAC region around 2000 BCE, not necessarily as rulers, but at least as troops of elite warriors with their effective war machines and social structures."

1. There is no proof that the Sintashta chariot was a "war machine'. In fact, it is vastly different from the Mitanni chariot. According to Anthony they were used by javelin throwers: "Second, steppe chariots were not necessarily used as platforms for archers. The preferred weapon in the steppes might have been the javelin...When horse-drawn chariots appeared in the Near East they quickly came to dominate inter-urban battles as swift platforms for archers, perhaps a Near Eastern innovation". So Vedic chariots were a Near Eastern innovation? And what were these effective social structures?

This also might be of interest. https://www.academia.edu/43434670/The_Introduction_of_the_Horse_Drawn_Light_Chariot_Divergent_Responses_to_a_Technological_Innovation_in_Societies_between_the_Carpathian_Basin_and_the_East_Mediterranean

2. Based on all the recent chronologies (Dubova 2020 and Gursan-Salzman) Hissar IIIB(2500-2200BCE) predates Sintashta by centuries.

"Due to the mass adoption of nomadic pastoralism and effective warrior societies"

Where? Yaz I and Late Grey Ware are pretty much continuations of older traditions. BMAC has been a warrior society since its conception from axes to depictions of defeated Jiroft enemies and Hissar even longer.

"With the desiccation that began around 1800 BCE, BMAC sites gradually became less and less populated, with its population likely joining the surrounding Indo-Aryan tribes to migrate with them"

There is no problem with your models. However, there are also models for Hasanlu and Alalakh that do not require steppe_mlba and use Yamnaya and Armenian sources instead. Which is more likely? Well, check out the following post 1500BCE samples from Turan:UZB_Bustan_BA:I11026

UZB_Bustan_BA:I4157

UZB_Bustan_BA:I4159

UZB_Bustan_BA:I5604

UZB_Bustan_BA:I5605

UZB_Bustan_BA_o1:I11521

TKM_Parkhai_LBA:I6668

TKM_Sumbar_LBA:I6675

Barely any steppe DNA makes it more likely that the steppe source of these west Asian groups is Yamnaya related.

The more likely scenario is when Late BMAC was collapsing there was perhaps a small movement from south to the steppes that brought I-I languages. "In the 2nd millennium BC settlement of Shagalaly II, between Kokshetau and Zerinda, in the Akmola region of northern Kazakhstan, T.S. Maljutina brought to light imported pottery of Oxus origin, or imitation, in stratigraphic association with Fedorovo and Alekseevka pottery" (Bonora 2020). See also, Taldysay and Kyzlbulak.