Genetic Impact of Iranic and Turkic Expansions from Central to West Asia

in the case of Kurds and Coastal Western Anatolian Turks

Contrary to what some might think, history should not be seen as merely composed of unlimited recurrences of limited patterns. There might be several paths that lead to the same or similar ends, and different explanations for the similar results in various conditions. Every situation should be taken care of individually, without forcing one of the potential conclusions of a specific scenario on every other one of them.

Having said that, it is also true that history is largely composed of recurrences of certain patterns. When it comes to expansion of languages, we roughly have two potential causes:

Migration of a certain group of people

Cultural dominance

Most of the time the expansion of a language (or a language family) depends on both of these. However, there are some arguments at least for some situations against the genetic continuity of these certain migrants. In this scenario the migrants at stake are seen as elite cultural dominators imposing their minority language on others without any considerable genetic contribution to the generations of the distant future. In this article we are going to explore whether this is the case for at least some of the Iranic and Turkic speakers of West Asia by using qpAdm, which is an academically accepted statistical tool for studying the ancestry of populations with histories that involve admixture between two or more source populations,1 with exclusively high coverage data (>1) from ancient samples. The list of the IDs of the samples that have been used as well as the qpAdm outputs of each chart, which include all the technical details needed to be sure of the validity of our models, can be found in the supplementary material.2

Iranic Expansions

It is generally accepted that with Andronovans' spread to Central Asia, this region became an Indo-Iranic speaking land in the Bronze Age. Their admixture with the native BMAC people (Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex) gave rise to new cultures3 such as Yaz I (1500-1000 BC), which is thought of as a proto-Zoroastrian Eastern Iranic culture because of its absence of graves. Yaz II (1000-700 BC), on the other hand, has been associated with the arrival of the Western Iranic speakers by the well-known Indologist Asko Parpola.4 We have a high coverage DNA sample from Yaz II (ID: DA382, cov: 1.79), and it can be basically modeled as below (Figure 1):

BMAC is mostly derived from Neolithic Zagrosians (0.65), with additional Western Siberian Hunter Gatherer (0.1) and Anatolian Farmer (0.25) ancestry. On the other hand, Andronovo could be seen as a successor of the earlier Sintashta Culture and therefore one of the extensions of Corded Ware people of Europe, which themselves had around 0.7 Western Steppe Herder and 0.3 Globular Amphora-related ancestry.5

Even if the association of Yaz II with the Western Iranic speakers is not as simple as Parpola proposed, we would still have good reasons to assume that this sample (DA382) could be seen as a proxy for the first Iranic migrants to Iranian Plateau and Zagros Mountains since we know that they have come from Central Asia. Iranic migrations to West Asia are generally assumed to began around the last quarter of the second millenium BC and continued throughout the Iron Age.6 Most of the modern Iranic languages of this region (such as Persian, Kurdish, Talyshi, etc.) are a result of these migrations.

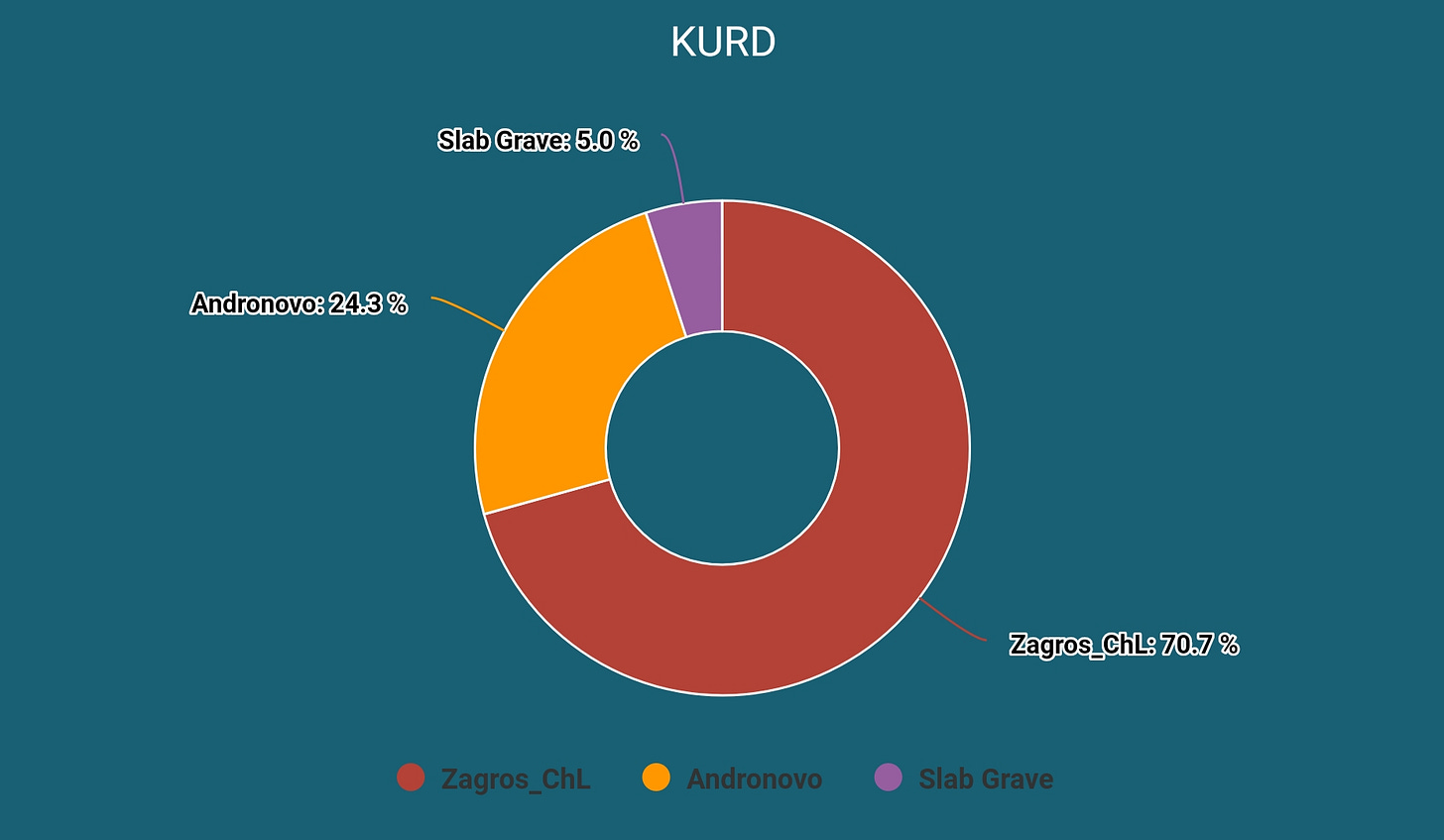

To represent modern Western Iranic speakers we have chosen eight Kurdish samples. Kurds can be modeled as below (Figure 2).

We have tried another model for Kurds with Andronovo component (in Figure 3) instead of Yaz II to see if the results are going to be consistent with the model in Figure 2. The results came out pretty coherent as the Yaz II sample itself is around 0.5 Andronovo-derived and therefore we may conclude that Kurds do descend significantly from Iranic nomads. The second model (Figure 3) does not need an additional BMAC source since BMAC shares a good proportion of ancestry with Chalcolithic Zagrosians. Slab Grave here represents the general East Asian contribution.

The rest of the article is still free and hopefully will stay so, but if you have read this far and appreciated what you have seen, please consider supporting my work on Patreon.

I am an archaeologist who mainly works on ancient Indo-Iranic cultures. I have published many articles and videos on archaeogenetics and ancient religious traditions in English and Turkish, some of which have been translated into Kurdish and Persian. Eliminating the fallacies surrounding these areas of research (that are generally born out of ideological sentimentality or romanticism regarding one's own ancestors) and providing reliable information in a clear, systematic and analytical way are my main objectives. I would be more than glad if you choose to support my work!

May the xᵛarənah be with you!

Turkic Expansions

In the Middle Ages Central Asia had already became a Turkic-speaking land for the most part instead of an Eastern Iranic one, and Turkification of Anatolia is strongly related to mediaeval migrations of various Turkic tribes from Central Asia; especially those who ran away from Mongolian invasions since their rapid movement made them less influenced by the Persian culture in comparison to Seljuks.7 When Oghuz Turks first began to settle in Western Anatolia, this region was mostly inhabited by Anatolian Greeks - who are considerably different from mainland Greeks when it comes to their genetics.8 9

To represent mediaeval Turkic migrants we have chosen two high coverage samples from mediaeval Central Asia, who probably had spoken Karluk Turkic (we do have a sample with ID MA2195 from mediaeval Anatolia which probably is an Oghuz sample and can be modeled approximately as 50-50 Slab Grave and Alan mixture, but since its coverage is not as high as Karluks’, we have decided to publish the models with Karluks. It should be noted that there is no considerable change in the results). Also we have used three high coverage Imperial Roman samples from early 1st millenium AD Italy who seem to be recent migrants from Anatolia as a proxy for pre-Turkic Western Anatolian Greeks. Please note that we do not know the exact genetic profile of pre-Turkic Western Anatolian Greeks but have decided that these specific Imperial Roman samples could be considered as a decent proxy. For modern Turkic speakers of West Asia we have chosen twelve Turkish samples from among the natives of coastal Western Anatolia. It might be a good idea to not forget that the genetic profile of native Turks from various regions of Anatolia can hardly be considered as homogeneous.10 11 As a matter of fact, Coastal Western Anatolian Turks are among the most Central Asian Turkic-admixed Anatolian Turkish groups based on genetic studies. The average amount of Central Asian Turkic genetic contribution detected among Central Anatolian Turks is about half or two-thirds of the one found among Coastal Western Anatolian Turks, and Turkish speakers from the provinces of northeastern corner of Anatolia like Trabzon, Rize and Artvin show no Central Asian Turkic genetic contribution at all.12 13

The mediaeval Karluks can be modeled as below (Figure 4):

Slab Grave Culture is probably the best candidate for the homeland of early proto-Turkic speakers14 and therefore we may conclude that the mediaeval Central Asian Turkics were approximately 50-50 mixture of proto-Turkics and Eastern Iranics (since “Andronovo+BMAC” can be considered as a trademark of post-Andronovo Iranics).

Coastal Western Anatolian Turks can be modeled as below (Figure 5):

To see if our model is reliable, we have tried another model for the Coastal Western Anatolian Turks with Slab Grave and Andronovo components in Figure 6. Proportions seem reasonable and coherent with quite good tail probabilities and standard errors. Therefore we may conclude that Coastal Western Anatolian Turks do have considerable mediaeval Turkic ancestry.

Conclusion

As a result of our qpAdm analyses guided by our current knowledge of history, we have concluded that at least some Iranic and Turkic speakers of West Asia have considerable genetic heritage descending from their linguistic forefathers. It seems like the “mounted nomad” pattern that we have first observed in Iranics has repeated itself with the Turkic migrations with comparable results.

It should be noted that our inferences for Kurds are consistent with a previous study by Dilawer Khan.15

Special thanks to David Wesolowski of Eurogenes Blog, Dilawer Khan of Eurasian DNA and Vikram Raj of The Archaeogenetics blog for their help with the technical details of qpAdm, and to Onur Dinçer of Anatolia-Balkans-Caucasus DNA Project, who has helped with the final editing to render this article as clear as possible and prevent misunderstandings.

Updates (13.03.2022)

An alternative model to Figure 1 (not necessarily a better one):

Figure 7: tail prob.: 0.863 std. errors: 0.042, 0.04, 0.014. To see the qpAdm output please click here. A simpler alternative model to Figure 2 with lower standard errors:

Figure 8: tail prob.: 0.288 std. errors: 0.029, 0.029. To see the qpAdm output please click here. Again, we have used exclusively high-coverage (>1) samples for Eblaites (IDs: ETM010, ETM012, ETM014, ETM023). Genetically they were a mixture of chalcolithic Zagrosians and Levantines; therefore it is reasonable to assume that they might resemble the pre-Aryan populations of the region to some degree. The model gives lower p-value when an East Asian proxy is added; which, given the fact that Kurds have some minor East Asian ancestry, makes us think of the possibility of Yaz II-related Early Iranics having some minor East Asian genetic heritage already (as it has been proposed in the Figure 7 above) and the Turkic contribution among the Kurdish samples we have analyzed might be negligible. Still, it should be noted that lower p-values do not necessarily indicate less realistic scenarios.

Recently a Kurd [now edited as Zaza (19.05.2022)] from Diyarbakır [now edited as Elazığ (15.09.2022)] (ID: YF097745) clustered within the same y-DNA subclade with DA382, the Yaz II sample we have, has been reported.16 Although it is a single case for now, it might be considered as a minor confirmation of Yaz II’s proposed relationship with Western Iranics. In any case, it should be noted that Y-Full tends to underestimate the age of haplogroups.

Harney, É., Patterson, N., Reich, D., Wakeley, J. (2021). Assessing the performance of qpAdm: a statistical tool for studying population admixture. Genetics, 217 (4), https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyaa045

Seven, N. (2021, December 5). Supplementary Material for Genetic Impact of Iranic and Turkic Expansions from Central to West Asia in the Case of Kurds and Coastal Western Anatolian Turks. Retrieved from https://drive. google.com/drive/folders/1xuuVK7Wxrr8j_97wAp4ZuwRS5Z6TjpyG?usp=sharing

Witzel, M. (2003). Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Western Central Asia. Sino-Platonic Papers, 129.

Parpola, A. (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press.

Narasimhan, Vagheesh M. et al. (2019). The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia. Science, 365 (6457), https://doi.org/10. 1126/science.aat7487

Kuzmina, E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Brill.

Arche Projesi. (2017, October 18). Marcel Erdal – Türk Dilleri Bölüm 1 [Video]. YouTube.

Sarno, S., Boattini, A., Pagani, L. et al. (2017). Ancient and recent admixture layers in Sicily and Southern Italy trace multiple migration routes along the Mediterranean. Scientific Reports, 7 (1), https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-017-01802-4

Stamatoyannopoulos, G., Bose, A., Teodosiadis, A. et al. (2017). Genetics of the peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval peloponnesean Greeks. Eur J Hum Genet, 25, https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg. 2017.18

Alkan, C. et al. (2014). Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa. BMC genomics, 15, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471- 2164-15-963

Hodoğlugil, U. et al. (2012). Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations. Annals of human genetics, 76 (2), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x

Kars, M. Ece et al. (2021). The genetic structure of the Turkish population reveals high levels of variation and admixture. PNAS, 118 (36), https://doi. org/10.1073/pnas.2026076118

Lazaridis, I. et al. (2014). Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature, 513 (7518), https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13673

Nezih Seven. (2021, May 21). Slab Graves and Proto-Turkics [Video]. YouTube.

Khan, D. (2020, December 25). Indo-Europeanization of Iran & Kurdistan: The Genetic Substructure of the Indo-Iranian Invaders. Eurasian DNA. https://eurasiandna.com/2659-2/

R-KMS149 Y Tree. (2022, March 13). YFull: NextGen Sequence Interpretation. https://www.yfull.com/tree/R-KMS149/

Hello Nezih, thanks a lot for this study.

If you have their file(s), can you also run other Western Iranian groups whenever you can? I want to see to which extent they differ from Kurds in specific percentages. (I know that qpAdm takes a lot of time to load up, but I would highly appreciate that.)

very good

my models:

Target: Kurdish(Central_Anatolia)

Distance: 0.9675% / 0.00967526

52.0 Zagrosian

24.0 Steppe_Bronze_Age

12.4 Caucasian

9.0 Levantine

2.4 Siberian

0.2 Ancestral_South_Indian

Target: Kurdish(Alewite)

Distance: 0.5957% / 0.00595689

53.8 Zagrosian

21.6 Steppe_Bronze_Age

10.0 Levantine

8.4 Caucasian

4.2 Siberian

1.0 Anatolian

1.0 Ancestral_South_Indian

Target: Iranian_Kurd_Kermanshah

Distance: 1.3320% / 0.01332046

59.4 Zagrosian

23.4 Steppe_Bronze_Age

6.2 Anatolian

4.8 Levantine

3.6 Siberian

2.6 Ancestral_South_Indian

Target: Iranian_Kurd_Urmia

Distance: 1.3167% / 0.01316679

53.0 Zagrosian

21.6 Anatolian

19.6 Steppe_Bronze_Age

4.6 Levantine

0.6 Ancestral_South_Indian

0.6 Siberian

Target: Iranian_Kurd_Kordestan

Distance: 0.8491% / 0.00849079

50.6 Zagrosian

20.0 Steppe_Bronze_Age

14.8 Levantine

6.6 Anatolian

5.0 Caucasian

2.2 Siberian

0.8 Ancestral_South_Indian

Target: Dersim

Distance: 0.7392% / 0.00739234

45.0 Zagrosian

20.4 Steppe_Bronze_Age

12.2 Anatolian

12.0 Levantine

7.0 Caucasian

2.6 Siberian

0.8 Ancestral_South_Indian

Target: Ezid

Distance: 0.5213% / 0.00521298

50.2 Zagrosian

22.0 Steppe_Bronze_Age

14.0 Levantine

6.6 Caucasian

3.6 Anatolian

2.0 Ancestral_South_Indian

1.6 Siberian

Target: Kurdish(Iraq)

Distance: 0.9377% / 0.00937668

56.4 Zagrosian

19.2 Steppe_Bronze_Age

10.0 Anatolian

9.8 Levantine

2.4 Caucasian

2.0 Siberian

0.2 Ancestral_South_Indian

Target: Syrian_Kurd

Distance: 0.7955% / 0.00795493

51.6 Zagrosian

24.4 Steppe_Bronze_Age

10.8 Levantine

9.0 Anatolian

3.2 Siberian

1.0 Ancestral_South_Indian